Simanaitis Says

On cars, old, new and future; science & technology; vintage airplanes, computer flight simulation of them; Sherlockiana; our English language; travel; and other stuff

APPRECIATING MATERIALS

LEARNING THAT NOTRE DAME RESTORATION was featuring medieval craftsmanship prompted pal and regular reader Bob Storck to share a similar tale from a classic barn raising: “I learned,” he wrote, “that joints were NOT shaped to perfectly match, but had small variations in gaps and dowel fitments based on which side faced sun, precipitations and wind weathering.”

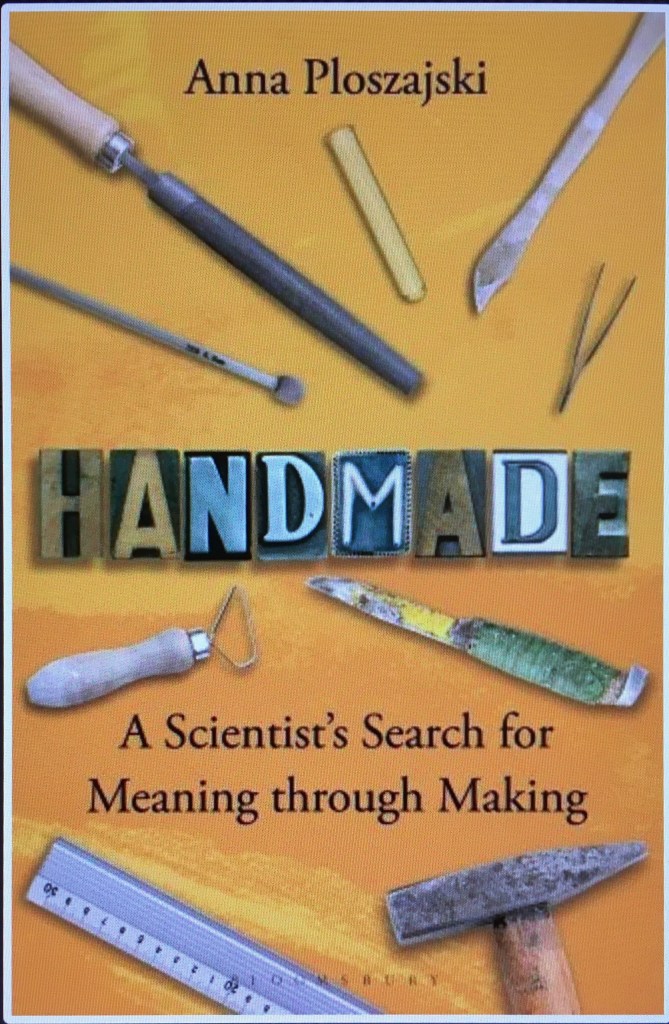

Coincidentally after reading Bob’s cogent observations, I encountered a review in AAAS Science of a book amplifying on such age-learned crafts.

Dorothy Jones-Davis reviews this book in AAAS Science, May 11, 2023. Here are tidbits gleaned from her review and from IndieBound’s comments.

IndieBound Observations: “Author and material scientist Anna Ploszajski journeys into the domain of makers and craftspeople to comprehend how the most popular materials really work…. Along the way, Anna builds a fuller picture of materials and their places in society, as well as how they have intersected with her own life experiences—from land racing on American salt flats to swimming the English Channel. She visits a blacksmith, explores how working with the primal material, clay, has brought about some of the most advanced technologies, and delves down to the atomic scale of glass to find out what makes it ‘glassy.’ ”

Science Review: Dorothy Jones-Davis writes, “The most important lesson in the book’s first chapter comes from Ploszajski’s realization that her hands-on experience with glassmaking offered her a greater understanding of the material. ‘Until I met the craftspeople behind it, glass was always looked through, never looked at,’ she writes.”

From the onset, I like Ploszajski’s gentle introspection.

“Yet,” Jones-Davis says, “even that identity is subject to interpretation. ‘Exactly the same material can range from being a priceless artefact to useless litter,’ muses Ploszajski in a chapter dedicated to paper. This brings forth the question: Can hands-on experience with a material change how one thinks about its value? Her answer is resoundingly yes.”

Dr. Ploszajski’s Trumpet. “Again and again, Ploszajski’s own experiences inform her narrative,” Jones-Davis observes. “In a chapter on brass, for example, readers learn about the material through the lens of the author’s prized trumpet. Here, she poses a philosophical question that reiterates how a material’s value is related to its use: ‘Would my trumpet still maintain its meaning if it weren’t made from brass, but instead of silver or plastic, or even of nothing at all?’ ”

The image of an “air trumpet” rendition is compelling.

Sheffield Steel. Jones-Davis says, “In chapter 3 (‘Steel’), Ploszajski recounts the story of ‘Women of Steel’—the hundreds of women who worked during World Wars I and II making tools and munitions in the steelworks of Sheffield, England.”

“Ultimately,” Jones-Davis writes, “Ploszajski succeeds in demonstrating that the act of making something can impart an appreciation for and understanding of the properties of the material from which it is made. ‘Just give it a go,’ she urges the reader. ‘There are tales to be told about these substances…. I hope that this book will inspire you to tell yours.’ ”

With all respect, sorta a philosophical Rosie the Riveter. ds

© Dennis Simanaitis, SimanaitisSays.com, 2023