Simanaitis Says

On cars, old, new and future; science & technology; vintage airplanes, computer flight simulation of them; Sherlockiana; our English language; travel; and other stuff

LIFE SPANS IN THE ANIMAL WORLD

DISCUSSIONS OF animal life spans include us too. There’s a Special Section on this topic in the December 4, 2015, issue of Science, published by the American Association for the Advancement of Science. Here’s a look at one of its articles, “Why We Outlive Our Pets,” by David Grimm. It’s a fascinating piece that confirms some things I thought I knew and dispels some myths as well.

As outliers in the data, Frenchwoman Jeanne Louise Calment lived to 122, the longest documented human age. By contrast, these days the average longevity for our species is 71. Creme Puff was a Texas cat that allegedly thrived on bacon, broccoli and heavy cream to a reported age of 38; the average feline life span, 15. Bluey, an Australian cattle dog, lived to 29, more than twice the average canine age.

In his Science article, Grimm quotes Daniel Promislow, an evolutionary geneticist at the University of Washington, Seattle, on animal aging: “A fascinating problem. It integrates behavior, reproduction, economy and evolution. If we can understand how to improve the quality and length of life, it’s good for our pets and it’s good for us.” Promislow is co-leader of the Dog Aging Project.

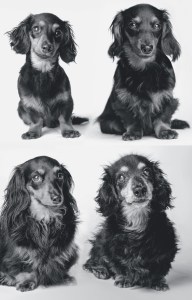

Lily, a long-haired dachshund, at 8 months, 2 years, 7 years and 15 years. This and other images from Science, December 4, 2015.

Animals age at different rates and, scientists suggest, for different reasons. Hypotheses in this regard get built up as well as torn down. For example, it was once thought that short-lived animals generate more tissue-damaging free radicals or have cells that stop dividing sooner. Further studies, though, suggest otherwise.

Another hypothesis was that the higher an animal’s metabolic rate, the shorter its life; in a sense, its body clock is racing. However, parrot hearts can beat as much as 600 times/minute, yet they outlive by decades plenty of species with slower hearts.

Mice furnish a clue that environment is an important factor. Another article in the Special Section, “Death-Defying Experiments,” by Jon Cohen, cites a laboratory dwarf mouse that lived a record 1819 days, thus missing its fifth birthday by only a week. By contrast, many mice in the wild are victims of predators before they reach 2 years old.

Steven Austad is a biogerontologist at the University of Alabama, Birmingham. He has a theory on animal longevity as well as an interesting background: Austad used to be a lion trainer in the early 1970s until his leg was injured by one of the big cats. He then got a Ph.D. and, during a postdoc, studied opossum behavior in Venezuela.

Marsupial aging proved an excellent test study. Notes Austad, “They’d go from being in great shape to having cataracts and muscle wasting in 3 months.” What’s more, he also observed other opossums living free of predators on a nearby island. These opossums seemed to age slower and live longer than their mainland counterparts.

The hypothesis that longevity favors the big guys has more going for it than metabolic rate. Large animals tend to live longer because they face fewer dangers. Austad postulates it’s not merely survival, but also the result of evolutionary perks over millions of years.

On the other hand, with dogs there’s a rule of thumb that small breeds outlive large ones, and to a great extent this is true. A 150-lb. Irish Wolfhound is old at age 7, whereas a 9-lb. Papillion can outlive the large dog by ten years. Evolution isn’t involved, because all breeds are relatively recent products of human husbandry. One reason for the aging difference is inherent health problems of larger dogs, German Shepherds’ hip dysplasia, for example.

Bowhead whales can live to more than 200 years. Image and video from National Geographic.

The bowhead whale, almost wiped out in whaling days but thriving today, has been identified as one of the longest-living mammals. Neck blubber of one captured in 2007 contained a harpoon manufactured around 1890.

In 2015, scientists mapped the whale genome and identified genetic aspects that could be responsible for its longevity. The bowhead has two specific gene mutations that enhance its repairing of DNA, thus giving the whale a resistance to cancer. There may also be physiological adaptations, such as a lower metabolic rate compared with those of other mammals.

Austad observes that large animals with no predators can invest resources in developing robust bodies and hardy immune systems. By contrast, mice and other prey need to put their energy into growing and reproducing quickly. Austad says, “You wouldn’t put a $1000 crystal on a $5 watch.” ds

© Dennis Simanaitis, SimanaitisSays.com, 2016

Related

3 comments on “LIFE SPANS IN THE ANIMAL WORLD”

Leave a comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Information

This entry was posted on January 13, 2016 by simanaitissays in Sci-Tech and tagged "Death-Defying Experiments" by Jon Cohen, "Why We Outlive Our Pets" by David Grimm, AAAS Science magazine, animal aging, Daniel Promislow University of Washington Seattle "Dog Aging Project", Steven Austad University of Alabama Birmingham.Shortlink

https://wp.me/p2ETap-3ZCCategories

Recent Posts

Archives

- March 2026

- February 2026

- January 2026

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

Creampuff, the cat! ________________________________

So there is some hope I will make it to 150 with my slow heart rate, but I better gain some weight! 🙂

Philippe,

Some experts say there are humans alive today who will reach 150. Maybe you’re one of them? Me? I’m trusting in red wine. Either way, it improves the life remaining.